Cultural/Biocultural Impact

Fishermen in Zanzibar

East Africa's coastal people have historically held deep connections with the ocean, coastal lands and forests, and an array of coastal/marine species. This connection exists because the coastal people are reliant on the natural resources of coastal/marine ecosystems to sustain their lives. For instance, timber from mangrove forests provide firewood and shelter (mangrove poles are used in the construction of traditional homes). Further, many marine/coastal species provide food. These resources also allow the people to make a livelihood. For generations, until recent times, local people have utilized coastal resources sustainably.

The significance of these resources can be seen culturally. Coastal people have always displayed reverence toward coastal/marine species through traditional rituals and customs (dance, storytelling, festivals). Their celebration of the long history of many species is deeply rooted and intertwined with their language and heritage.

Today, over-exploitation of natural resources in East Africa's coastal/marine environments has caused significant food shortages regionally. Quite naturally, over-exploitation has also led to the steady erosion of long-held traditions and customs in coastal East Africa that are reliant on marine and coastal resources. At risk is a longstanding traditional knowledge and set of practices that are vital for health, security, and the survival of the traditional coastal communities. As such, a variety of species as well as entire cultures in coastal East Africa are presently simultaneously endangered as the continued loss of important species results in the loss of tradition, language, and subsistence for coastal populations. It is imperative to safeguard the bio-cultural heritage of this region and preserve important culturally sustainable practices.

Endangered Species, Endangered Societies

Subsistence

Fish are the main source of protein for much of the region. Some species are so scarce that the poor can no longer afford them. In fact, they can not afford to buy even common, culturally important species because the price is so high due to limited supply. In addition to fish, the meat and eggs of green turtles, themselves rapidly disappearing, have served as a source of protein and are highly valued foods.

A decline in marine life in the Indian Ocean off the Kenyan coast is well documented. Indeed, East African waters have largely been fished out. This is attributed in large part to mangrove deforestation, overfishing, and destructive fishing practices.

Mangrove forests are productive ecosystems. They play several important ecological roles along the coast by providing breeding grounds for a variety of coastal species. The link between mangrove deforestation and its negative impact on fisheries and other important marine species is well documented. Similarly, a decline in near-shore fisheries in coastal East Africa is very evident.

Kenyans must now travel a much longer distance by sea to gather fish, as the local marine life has been so reduced. Yet, most Kenyans do not have the means to travel the distance necessary to gather fish. Therefore, the Kenyan coastal populations and consumers of their products have been and will continue to be negatively affected by the loss of natural resources. This trend cannot continue without serious consequences to overall species biodiversity and severe food shortages, endangering the lives and societies of the coastal Kenyan population.

A decline in marine life in the Indian Ocean off the Kenyan coast is well documented. Indeed, East African waters have largely been fished out. This is attributed in large part to mangrove deforestation, overfishing, and destructive fishing practices.

Mangrove forests are productive ecosystems. They play several important ecological roles along the coast by providing breeding grounds for a variety of coastal species. The link between mangrove deforestation and its negative impact on fisheries and other important marine species is well documented. Similarly, a decline in near-shore fisheries in coastal East Africa is very evident.

Kenyans must now travel a much longer distance by sea to gather fish, as the local marine life has been so reduced. Yet, most Kenyans do not have the means to travel the distance necessary to gather fish. Therefore, the Kenyan coastal populations and consumers of their products have been and will continue to be negatively affected by the loss of natural resources. This trend cannot continue without serious consequences to overall species biodiversity and severe food shortages, endangering the lives and societies of the coastal Kenyan population.

Livelihood: Economic Ramifications

In addition to subsistence, coastal people depend on the sea for their livelihoods. In fact, fishing is a the primary livelihood for most coastal communities. Recent fish shortages due to the cumulative impact of overfishing, destructive fishing methods, mangrove clearing, and other habitat loss has made fish scarce, therefore prices exorbitantly expensive. In Mombasa, Kenya, many locally owned fish shops and fish processing plants have closed down due to shortages of fish, while local investments in fishing industries have died out along with the fish stocks.

Further, throughout East Africa, women run small fish businesses (buying fresh fish, frying it, and selling the fried fish in markets) to supplement the meager income of their fishermen husbands. These types of businesses give the women a source of pride and a greater sense of self-sufficiency. Fish shortages in the recent past have made it more difficult for women to start and/or maintain such businesses.

Further, throughout East Africa, women run small fish businesses (buying fresh fish, frying it, and selling the fried fish in markets) to supplement the meager income of their fishermen husbands. These types of businesses give the women a source of pride and a greater sense of self-sufficiency. Fish shortages in the recent past have made it more difficult for women to start and/or maintain such businesses.

Cultural Practices: Language

The Swahili language, also called Kiswahili, is spoken by an estimated 120-150 million people and, after Arabic, is the most widely understood language in Africa. Swahili is either a national or an official language in about five East African countires: Kenya (national), Tanzania (official), Uganda (national), Comoros (national) and DRC (national). Swahili is also spoken in Rwanda, Burundi, and southern Somalia.

People who speak Swahili as their primary language are referred to as Waswahili. Oftentimes, reference to "Swahili" denotes the language spoken of a diverse population of coastal people; it does not denote any particular ethnic or tribal unit. Indeed, there are numerous tribal units along coastal East Africa speaking diverse languages. Swahili gives these tribal units a common language.

From a tribal or cultural standpoint, however, there is a distinct community of Swahilis. They do not form one tribe, but the community can be defined as coastal, first-language speakers of Swahili who share a similar culture and traditions (the true Swahili). These coastal people are quite few in number.

The word Swahili is rooted in Arabic sawāḥilī (a plural form of an Arabic word meaning “of the coast”). The language, which reflects and dates back to early contact with Arabian traders, is in decline. For example, Kenya uses foreign languages such as English in schools. In recent years, as Swahili has become less significant, Swahili speakers are small and declining communities. Swahili also has several dialects associated with the ancient coastal city states. As English and standard Swahili are emphasized in schools, these dialects are also increasingly endangered.

The loss of the language is exacerbated by the loss of native plant and animal species. Simply, as species die out, so do their native names in the Swahili language. Such loss of language carries forth to younger generations. It is of grave concern, particularly to indigenous elders who pass on traditional knowledge to younger generations both verbally as well as expedientialy. The loss is particularly pronounced in words associated with endangered, threatened, or extinct species that now primarily exist in song, story, and poetry.

People who speak Swahili as their primary language are referred to as Waswahili. Oftentimes, reference to "Swahili" denotes the language spoken of a diverse population of coastal people; it does not denote any particular ethnic or tribal unit. Indeed, there are numerous tribal units along coastal East Africa speaking diverse languages. Swahili gives these tribal units a common language.

From a tribal or cultural standpoint, however, there is a distinct community of Swahilis. They do not form one tribe, but the community can be defined as coastal, first-language speakers of Swahili who share a similar culture and traditions (the true Swahili). These coastal people are quite few in number.

The word Swahili is rooted in Arabic sawāḥilī (a plural form of an Arabic word meaning “of the coast”). The language, which reflects and dates back to early contact with Arabian traders, is in decline. For example, Kenya uses foreign languages such as English in schools. In recent years, as Swahili has become less significant, Swahili speakers are small and declining communities. Swahili also has several dialects associated with the ancient coastal city states. As English and standard Swahili are emphasized in schools, these dialects are also increasingly endangered.

The loss of the language is exacerbated by the loss of native plant and animal species. Simply, as species die out, so do their native names in the Swahili language. Such loss of language carries forth to younger generations. It is of grave concern, particularly to indigenous elders who pass on traditional knowledge to younger generations both verbally as well as expedientialy. The loss is particularly pronounced in words associated with endangered, threatened, or extinct species that now primarily exist in song, story, and poetry.

Cultural Practices: Fishing Villages

Fishermen's Village, Zanzibar

The East African coastline is riddled with a number of a local fishing villages and dhow building sites. For some, these fishing camps are temporary homes during high fishing seasons. For others, such boat villages are permanent homes. Generally, the men in these villages engage primarily in fishing and dhow making, while the women engage in traditional handicrafts, making such items as straw mats woven from palm leaves and ropes of coconut. In these villages, it is customary for the men to go on fishing trips for several days at a time. Their livelihood and way of life are, therefore, dependent on an ample supply of fish.

Cultural practices: Medicinal Practices

Green Sea Turtle

Coral Reefs

Perhaps the greatest and most unsung value of the coral reefs are the medicinal benefits that we are just beginning to explore and understand. Like rainforests, reefs have a rich potential of unknown compounds that could have promising medical applications.

Marine Life

A WWF survey of 1996 medical wildlife resources revealed that meat, oil, bones, and tusks of dugongs are used to cure a variety of ailments, including arthritis, labor pains, and tonsillitis. In fact, the inhalation of both powdered dugong bones and the smoke from burning dugong bones is believed to cure a multitude of ailments from tooth aches to labor pains. Pieces of tusk and bone are also worn by children as charms to ward off evil spirits. Because of these uses, the dugong is referred to as the Queen of the Sea in the Lamu area, Kenya.

Sea turtles have long been a resource of cultural significance to coastal communities in Kenya. For centuries green turtle eggs have served as an aphrodisiac, a protection to the body when fishing (particularly diving), and a community’s protection from evil spirits. Turtle meat and oil have also been used to treat ailments such as asthma, liver problems, muscular pain, and sexual potency.

Cultural Practices: Use of Mangrove for Building Materials

Local traditional house made out of mangrove pole

Mangrove forests are productive ecosystems. Mangroves produce timber resources that are important to the coastal communities. Coastal Kenyan populations are heavily reliant on mangroves to sustain their lives (timber, firewood), to promote cultural and traditional practices (building material for homes), and to make a living (selling mangrove poles and timber).

Cultural Practices: Traditional Methods of Hunting and Fishing

Ramora (sucker fish) on a Sea Turtle

Fishing is a very important tradition among Swahili men. Traditional methods of fishing include: fish traps, spearfishing, netting, and caging. Caging techniques vary; however, many caging techniques take advantage of the ebb and flow of the sea to capture marine life (techniques that have evolved over centuries). So, when tides come in, fish are caught up in the maze-like cage; when the tides goes out, fish are trapped in the cage.

Other traditional forms of collecting marine life include the use of remora (shark suckers, a sucker fish) as a substitute for conventional fishing rods and hooks. In Lamu (Kenya), for instance, sea turtle meat is fed to shark suckers (remoras) to get them accustomed to the smell and taste. Once training is complete, a line is attached to the remoras as they are sent from the boat to hunt down sea turtles. After a remora has found its prey, it sticks itself onto the sea turtle, and the fisherman pulls up his catch.

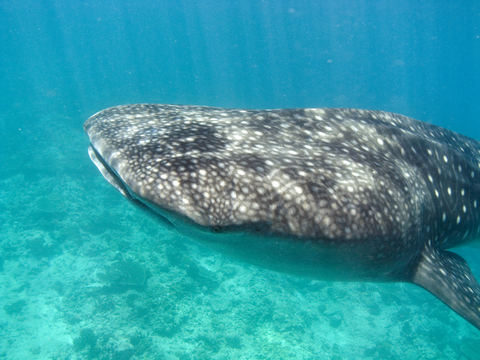

Importantly, local culture forbids the waste of any animal part after catching the animal (particularly if the catch is incidental). Local culture encourages using all parts of animals. For example, if a dugong is caught, local people will use dugong fat as fuel for lamps. The liver from whale sharks is used to make liver oil, which is used to protect wooden boats from ship-worms and other degradation.

Other traditional forms of collecting marine life include the use of remora (shark suckers, a sucker fish) as a substitute for conventional fishing rods and hooks. In Lamu (Kenya), for instance, sea turtle meat is fed to shark suckers (remoras) to get them accustomed to the smell and taste. Once training is complete, a line is attached to the remoras as they are sent from the boat to hunt down sea turtles. After a remora has found its prey, it sticks itself onto the sea turtle, and the fisherman pulls up his catch.

Importantly, local culture forbids the waste of any animal part after catching the animal (particularly if the catch is incidental). Local culture encourages using all parts of animals. For example, if a dugong is caught, local people will use dugong fat as fuel for lamps. The liver from whale sharks is used to make liver oil, which is used to protect wooden boats from ship-worms and other degradation.

Cultural Practices: Legend and Storytelling

|

Dugong Dugongs have played an important role in legends in Kenya, and the animal is known there as the "Queen of the Sea.” The female's highly developed teats resemble human breasts. The dugong, in legend, is known as the mysterious lady of the sea, a hybrid fantasy of woman and sea creature, believed to be the mermaid herself. Whale Shark In Kiswahili, the whale shark is called “papa shilling,” which loosely translates to “shark covered in shillings” (shilling is a silvery coin, used as the local currency). Legend has it that God was so pleased when he created this beautiful fish that he gave his angels handfuls of gold and silver coins to throw down from heaven onto its back. As a result, the whale shark has shimmering markings on its back side. When it swims swim near the surface, the sun reflects off its back toward the heavens (peponi). Dolphins There are several stories and myths surrounding dolphins in East African communities. For example, many tell of dolphins protecting ship-wrecked individuals from sharks, then leading these poor lost souls back to land. |

Cultural Practices: Jewelery, Ornamental Uses of Marine Resources

Shop on Beach in Kenya

Shops line the beaches of Kenya, Tanzania, and Zanzibar, selling jewelery and other trinkets made of marine resources. Sea shells are bound together to form necklaces and bracelets. The tusks of the dugong are fashioned into ornaments and jewelery such as rings and nose plugs.